What is the best ammo for your M1 Garand?

Every firearm, no matter how flawed or unpopular it may have been, is important because it represents at least a little piece of history. By that measure, the M1 Garand is one of the most important weapons ever to have existed. Regardless of which side someone might have found themselves fighting on during the Second World War, they would have had to have been aware of the first standard issue semi-automatic rifle.

Today, thousands of American shooters are lucky enough to have one of these Garands as part of their personal arsenal. It's a piece of history that's can be a showpiece and quite often, it's a still functional range or hunting rifle. If it works, why not pick up some ammo and fire it, right?

Details About M1 Garand Ammo

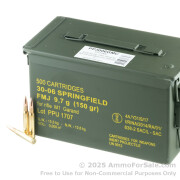

Your M1 Garand fires 30-06 Springfield ammo - you might also hear this referred to as .30 M2, more of a military designation. The original military loads came in a case of 480 rounds, packed in two, 240-round cans. Today, we're lucky to have manufacturers making specific loads optimized for use in the heavy duty Garand rifles.

Typically, an M1 is used with en block clips to load the ammo into the rifle. These clips hold 8 rounds each and, when we're lucky, you'll find some surplus loads available still loaded onto the clips.

Who Developed the Garand?

The M1 Garand (which pronounced correctly rhymes with “errand”) takes its name from its designer John C. Garand. The Quebecois learned English as a young man while sweeping the floors at a textile mill, and went on to join Springfield Armory in 1919. There he spent 15 years developing a weapon with a gas system capable of ejecting a spent cartridge and feeding a new one into the chamber, all in one action. He would patent the “Semiautomatic, Caliber .30, M1 Rifle” in 1932, just in time for some serious business that was about to take place.

Allies made approximately 5.4 million M1 Garands during WWII, which were used by all branches of the U.S. Military as well as several of our nation’s allies in the conflict. The British notably did test the M1 Garand out, but rejected it for the reason that it was less reliable in the mud than their Lee-Enfield. The M1 Garand endured into the Vietnam War, but in 1965 it was officially replaced by the M14 (with the exception of some sniper models). The rifle remains in use for combat by various countries throughout the world today. The United States Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon still uses the M1 Garand as well, although if called into combat those Marines would probably not bring along their antiquated, 10.5 pound ceremonial rifles.

How M1 Garands Work

The M1 Garand is a gas operated, rotating bolt semi-automatic rifle chambered in 30-06, although the U.S. Navy used a model chambered in 7.65x51mm after WWII ended. Its internal magazine is fed via an eight round en bloc clip, which is inserted through the top of the rifle. The M1 Garand is capable of firing up to 50 rounds per minute, with an effective range of 500 yards, and comes with standard adjustable aperture rear and wing protected post front iron sights. One of the M1 Garand’s strongest suits is the ease with which it can be broken down. Without the aid of tools a soldier could field strip their weapon in a matter of seconds, a huge advantage to have on the battlefield.

Of course, the greatest advantage the M1 Garand presented was its rate of fire. Its semi-automatic operation and relatively gentle recoil permits its shooter to fire essentially as fast as they can pull the trigger. The aforementioned 50 rounds per minute is not theoretical, but rather a practical measure of what a soldier could realistically achieve with the right training.

The gas system that the original M1 Garand implemented was relatively complicated, and soon swapped out with a more straightforward mechanism that did away with the gas trap in favor of a drilled gas port. An existing rifle that wasn’t retrofitted in this fashion is rare indeed, and likely to be a collector’s prized possession. Interestingly, the M1 Garand used a stainless steel gas tube, which was protected with stove blackening. One major drawback of that design was that when the blackening wore off it would reveal a gleaming muzzle that the shooter’s enemies could find easier to spot in the distance.

Including the T1 prototype, there have been three dozen variants of the M1 Garand designated by the U.S. Army. Most never saw active duty. Notable variants include the M1C and M1D which include mounting systems for telescopic sights, and the M1E5 and T26 which were known as “Tanker Garands.” Those variants’ barrels measured 18” long instead of 24”, and the M1E5 further included a folding buttstock. The T20E2 was capable of automatic fire and implemented a 20 round magazine, although its arrival late into WWII meant that it too never saw active duty.

It is only natural that so influential and ubiquitous a rifle would spawn a number of derivatives. The M1 carbine, which features a 18” barrel and weighs less than six pounds when loaded, was developed to be less cumbersome to American troops. The M14 would itself take design elements from both the M1 Garand and the M1 carbine. The Japanese took heavy inspiration from the M1 Garand when they developed their own Type 4 rifle, which was chambered for 7.7x58mm Arisaka and featured a 10 round internal magazine. No Type 4 rifles would enter service before the war ended, however.

Surplus M1 Garands are still popular among American shooting enthusiasts, and as of 2019 are readily available for under $2,000. Whether you would subject your M1 Garand to the rigors of hunting, only let it out for a little casual range shooting here and there, or give it a definitive oiling and set it aside to preserve a piece of important history, the rifle is very much worth owning. Even M1 Garands that have been beaten up by a lot of action can be greatly revived with handsome new wooden stocks, which are freely available. But some people consider a firearm’s marks of abuse to be integral to their character. You may rightly wish for your M1 Garand’s nicks and scratches to continue to exist, to tell their stories to future generations.

Loading, please wait...

Loading, please wait...